(This chapter and the second one will mostly be an edited version of what I posted last year.)

*

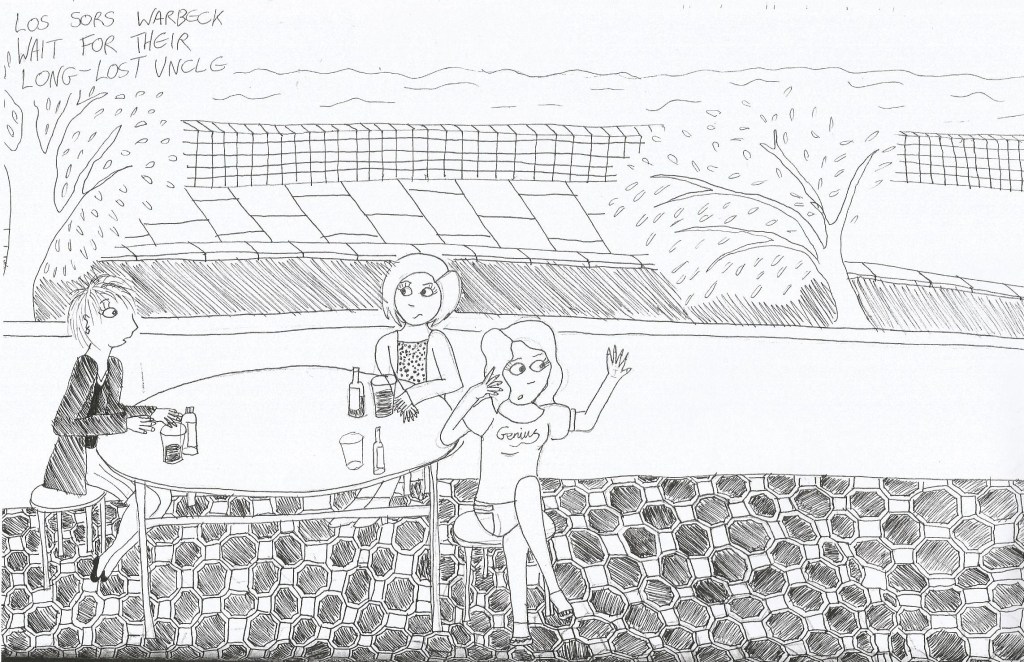

Sally and her sisters were marooned, cut off from any human contact and stranded in the icy expanses of deep space. Sure, to anyone watching from the outside, it would have looked like they were sitting on a sunny terrace in front of a nice café, but Sally knew how she felt.

“I still don’t know why he couldn’t have met us at the station,” said Jeanette, shielding her eyes from the sun. They’d got to that stage in waiting where Jeanette suddenly forgot how to keep still. She’d been shifting about on her seat, playing with her empty drink bottle, and examining her nail varnish for any chips that might have appeared in the last thirty seconds. Sally didn’t know how long they’d been there exactly. All she knew was that it had been enough time for her to drink four bottles of Pepsi. If Mum had been there, she’d have made her stop at two, but she wasn’t, so Sally was going to make her own fun.

“I’m sure he would have if he could have,” said Rube, who was meant to be in charge and looked like she really, really wished she wasn’t.

“But he works from home, right? How hard can it be to get away?”

“I don’t know,” admitted Rube. She’d had her hair cut short a few weeks ago, and her face looked really lonely without it. “I’m sure he’ll be here soon.”

“How soon is now?” muttered Jeanette, which didn’t make any sense, but at least she wasn’t moaning anymore.

Sally stayed quiet and looked at the trees on the other side of the road. Strange, alien-looking trees, too thin and too light a shade of green. Not like the trees at home.

She’d never been to Uncle Colwyn’s place. None of them had. He’d been round theirs for Christmas a couple of times, but they’d never actually seen the house. It was called Dovecote Gardens (which was another thing that put Sally off- normal houses didn’t have names), and Mum had grown up there. She’d said it was a wonderful old house with a lot of personality. That probably meant it was full of spiders. They’d probably burst out of your mattress if you wriggled too much in your sleep.

“What does Uncle Colwyn do for a living, anyway?” asked Jeanette.

“He maintains the grounds and things around the house,” said Rube, “I think Mum said some of it was owned by the National Trust.”

“Oh yeah, sounds really demanding. Obviously he wouldn’t be able to spare fifteen minutes to drive down and pick us up. I completely understand now.”

“Look, I’m just telling you what Mum told me.”

“I know, but you’d think she’d have told us more, right?” Jeanette wrapped a strand of long blonde hair around two of her fingers, and gently touched them to her lips. “Like why we had to go off to the other side of the country for the whole summer. And would it have killed her to tell us about it before the last week of term?”

Rube shrugged unhappily.

They’d had three days to get ready. Three days to pack their worldly belongings before leaving their hometown behind and going into outer space. And Uncle Colwyn hadn’t even been here to meet them. The least he could have done was be here. At least he’d have been familiar.

Jeanette let out a short burst of air, and smiled a little sheepishly. “Ugh. I don’t even know why I’m complaining. A whole summer away from that jackass Monessa is a whole summer away from that jackass Monessa.” She rolled her eyes. “And who names their daughter Monessa anyway?”

“It’s a saint’s name,” said Rube.

“Why do you hang out with her if you hate her so much?” asked Sally, who’d had to listen to Jeanette whingeing about Monessa for the last six months.

Jeanette waved her arms. “It wasn’t my decision! Zainab had clarinet lessons with her, they hit it off, and now suddenly she’s part of our group and we all have to listen to her repeating jokes from KFC adverts all day.”

A taxi parked on the corner nearest the terrace, and a man got out and looked around. He checked a piece of paper in his hand, and walked over to them. “Excuse me- is one of you Ruby Warbeck?”

Rube raised her hand as if they were still in school. “Yes?”

“I’ve got a letter from your uncle.” He handed her the piece of paper, which turned out to be a little white envelope. Rube opened it daintily with one fingernail (a trick that Sally had always envied), and took out the letter inside.

“Colwyn says he’s been held up at work,” she told Sally and Jeanette, after skimming it for a couple of seconds, “He’s paid for a taxi to take us to his, and he promises to be there by this evening.”

Jeanette let out an exasperated snarl. “Goddammit, I thought he worked from home!”

The taxi driver shrugged.

Jeanette might have been disappointed, but Sally wasn’t surprised in the least. This was exactly what she’d come to expect from deep space. She reached down, picked up her suitcase, and headed for the next galaxy.

*

Dear Ruby,

I’m so sorry to leave you and your sisters waiting- you must think that I’m the rudest man alive. Something came up at work, and there was no getting around it. Please find the front door key sellotaped to the back of the envelope. I’ve paid for your taxi to the house (complete with tip, so you don’t have to worry about that), and I hope to see you later this evening.

I know the circumstances aren’t the best, but, still, I’m very excited to have the three of you up at the house for the summer. There are a lot of people I’d like you to meet.

Yours sincerely,

Colwyn Ballantine

In the back of the taxi, Rube felt Jeanette nudge her arm. “I’m pretty sure that at this point, the Always logo is permanently stamped on my arse,” she whispered.

Rube made a face, and shushed her. She had a point, though- between the train and the café, they’d been sitting down most of the day even before the taxi had got stuck in traffic. It wasn’t comfortable for anyone, and Jeanette probably had it worst.

“Apologies for the delay, ladies,” said the taxi driver (who, thankfully, didn’t seem to have heard what Jeanette had said), “I think there must have been an accident up ahead.”

“That’s OK,” said Rube. Jeanette and Sally’s faces said different, but she ignored them.

“We shouldn’t be much longer. We just need to take the next left, and then it’s a straight line to Dovecote Gardens.”

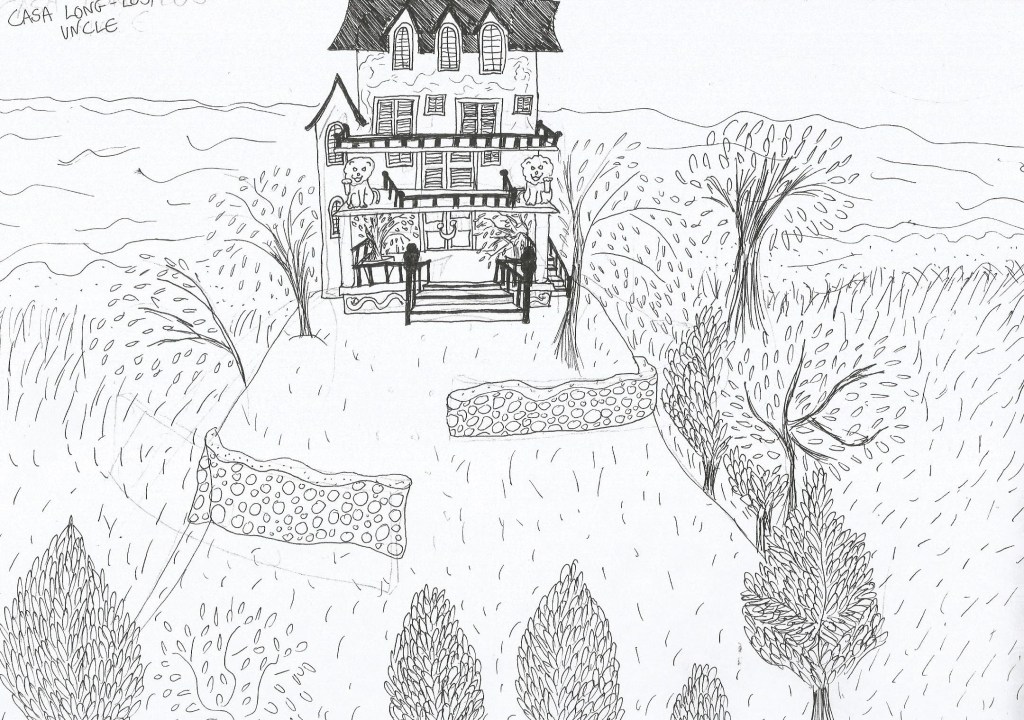

Dovecote Gardens was the official name of Uncle Colwyn’s house, but apparently the gardens themselves were the really interesting part. There were statues, topiaries, plants from all over the world, all spread out over the hill and the surrounding fields. That was what Uncle Colwyn spent his life maintaining, and that was why Rube was a bit more sympathetic about his being held up than Jeanette was. ‘Working from home’ probably meant something a lot different when ‘home’ stretched out for half a mile.

Technically, Colwyn was Mum’s cousin rather than her brother, but she’d spent most of her childhood living with her aunt and uncle, so it more-or-less amounted to the same thing. They’d all moved to Dovecote Gardens when Mum was a teenager. Colwyn’s mother had inherited it from her father. Or, wait, maybe it was the other way round? Rube didn’t remember. Somebody had inherited it from somebody, that was the point. It had been in their family for over a hundred years.

Sally was leaning against the car window, her ear pressed against the glass as if she was trying to hear the sea. “I’ve worked it out,” she said gloomily, “Five weeks is thirty-five days. We’re going to have to wake up in Dovecote Gardens thirty-five times before we can go home.”

“Thirty-four,” said Jeanette, “Today’s Saturday. We’re going back on the Friday.”

“OK,” said Sally, “What’s twenty-four times thirty-four?”

“Er… Well, twenty times thirty is six hundred…”

Rube wanted to tell Sally to stop thinking about their holiday as if it was a prison sentence, but, if she was honest with herself, Rube wasn’t thinking of it as a holiday, either. It felt more like they were being sent into hiding. She didn’t know exactly what Colwyn meant by, “I know the circumstances aren’t the best,” but she could make an educated guess that it had something to do with Dad.

Not long after the taxi driver turned left, they saw the hill in the distance. “That’s the house, right there,” said the driver, nodding towards the little blur of black and cream at the top, “You’ll have a good view of the sea.”

They drove up to a ten-foot hedge with an arch carved into it to allow the road to go through. Once they’d passed it, Rube glanced behind, half-convinced that the arch would have closed up behind them. It was a lot neater than the thorn bushes in ‘Sleeping Beauty,’ but Rube didn’t know if that meant they could trust it. A lot of things were neat.

At first, all they passed were tall, conical trees that made Rube think of the spade symbol you got on cards, spaced out along the side of the road at two-yard intervals. As they went on, though, there was more. Every shade of green you could think of, with occasional flashes of pink and blue. Rocky streams with miniature waterfalls and wooden bridges. Little black ponds covered in reeds and lilypads, like in a cartoon. What looked like a hedge-maze, off in the distance. Fountains with three or four layers, splashing water that looked like an impossible shade of blue. Clusters of tall, leafy willows casting ominous shadows across the grass. And throughout it all, little white garden walls wound through it, like someone had put a marble net over the whole thing.

The first things Rube noticed, when she finally saw the house close-up, were the two marble lions perched on the roof of the veranda, each with a raised front paw and a snarl on its lips. Rube wondered how old they were. They looked like they’d been made out of the same rough, off-white stone as the rest of the house, but there wasn’t any weathering on their faces. You could still see every whisker, even from four metres below them.

“Does Uncle Colwyn drive?” asked Jeanette, looking around for a parking space or a garage, “He must do, right? He’s barely walking-distance from his front gate, let alone the shops.”

“I don’t know,” said Rube. She seemed to remember him taking the train down to visit them at least once.

The house was four storeys, all white stone, black railings and wooden shutters, and Rube found it hard to imagine what it must be like to live there alone. Maybe that was why Colwyn had been so quick to invite them to stay- the company of three annoying nieces was better than no company at all.

They went up to the veranda, and Rube unlocked the door. When she got it open, she was relieved to find that the house smelled nice- warm wood and fresh air. It wouldn’t have been a good sign if she’d smelled mould or dust. Or old food, which you could smell at one of her friends’ houses back home and which meant that Rube couldn’t spend more than five minutes in there without gagging.

They walked inside, and saw that the whole bottom floor seemed to be one room. You came through the door to the living room, and the dining table and kitchen unit were at the back, behind the staircase. At various points around the walls, there were French windows, leading out to the gardens.

“I’m sure there’s some kind of feng shui thing about not putting the stairs right across the room like that,” said Jeanette.

“I don’t think that’s how it’s pronounced,” Rube replied. She walked over to the coffee table opposite the sofa, and found another note from Uncle Colwyn.

Dear girls,

I’m so sorry I couldn’t be here this evening. I’ve prepared a salad for dinner, but if you’re not in the mood for that, there’s plenty of other food in the fridge. I hope to be back tomorrow morning at the latest.

Yours,

Colwyn

Rube walked through to the kitchen, and found the salad bowl in the fridge, covered with clingfilm. “This looks nice,” she told the other two. She’d probably have said it anyway, just to be encouraging, but it did look nice. It was one of those salads with cheese and fruit thrown in, as opposed to Mum’s salads, which were usually just cucumber, lettuce, tomato, and maybe some red onions if you were lucky.

Rube turned round to put it on the table, and saw the horse.

Not an actual, flesh-and-blood horse, obviously, though it had made her jump just as much as if it was. This horse looked as if it was made out of wood and wicker. It was a head mounted to the wall like a hunting trophy from the bad old days, and underneath was a label saying Falada.

When Jeanette came over to see it, she made a little impressed noise in the back of her throat. “Why do you think it’s called Falada?”

“It’s from a fairy tale,” explained Sally, “The one about… um, there’s a kidnapped princess, and they kill her horse so it can’t tell anyone who she is, but then its head carries on talking anyway…” At this, she eyed the horse nervously, as if she expected it to start speaking there and then. It wasn’t just her, either- Rube found herself checking around the base for any microphones or mechanical bits.

After a moment or two, by which time they were all reasonably certain that they didn’t have a talking wooden horse on their hands, Jeanette leaned forward and patted it on the nose. “I wish we had something like this at ours. Do you think he’ll tell us where he got it?”

“I think maybe he made it himself,” said Rube. She didn’t know why she thought that, but she did. Maybe it was something about the unevenness of the wicker. Or maybe it was just comforting to think of Uncle Colwyn as the kind of guy who’d spend weeks on end making something sweet and odd like this. It wouldn’t be so bad to spend five weeks with a man like that.

Jeanette straightened up. “Anyway. Salad?”

“Salad,” agreed Rube, and they went to sit at the dining room table.

*

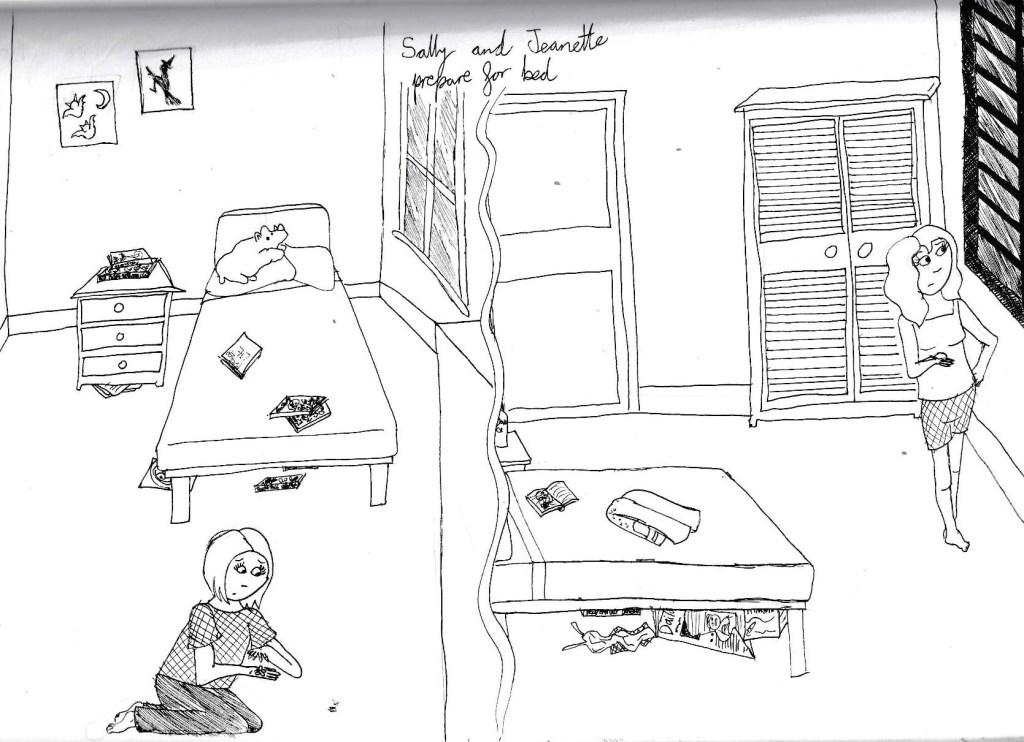

There had been a whole bunch of bedrooms to choose from, and Jeanette had picked the one with the imposing, black-framed window that stretched up to the ceiling. It gave the place a gothic look, which seemed appropriate when you were sent off to a big, empty mansion to visit a long-lost relative. Just as long as no-one got locked in the attic or forced to marry a wicked duke.

She’d been worried that she’d have to share with Sally. Even after they saw that there were enough rooms for the three of them, she’d worried that Sally might say she’d feel better with Jeanette or Rube in the same room as her. And Jeanette would have been the obvious choice, being three years older instead of five and a half, and she wouldn’t have been able to complain or refuse without feeling like a selfish jerk. Sally had been anxious about this whole trip from the start. If she’d needed her big sister to keep her company, then big sister would just have had to to swallow her desire for personal space and do the right thing. But it hadn’t happened. Sally was in the room next door, close enough to shout if she needed anything, and Jeanette was in here. It was the first stroke of luck she’d had all day.

In a way, though, she was glad that Uncle Colwyn hadn’t been there when they arrived. After a journey like that, the last thing you wanted to do was make polite conversation with a guy you hadn’t seen in years. After dinner, Rube and Sally (who saw her every day, and had been stuck on a bus with her for three hours on top of that) had let her go upstairs for a shower, then pick a bedroom and stay there. Uncle Colwyn probably wouldn’t have.

Still, where was he? They weren’t going to find his body in the cellar or something, were they?

She shouldn’t think like that. It was tempting fate.

She was pretty sure this house didn’t have a cellar, anyway.

Jeanette turned out the light and got into bed. The big, black window loomed in front of her. There weren’t any curtains, so all you could see from the bed was the sky. You could actually see the stars from here. You couldn’t at home.

*

If Sally had been able to get to sleep on time, she’d never have seen it. But she’d hated the idea of lying here in the dark thinking about things, so she was reading instead. It didn’t make her feel much better. She’d thought that maybe she could forget about what was going on in real life if she got absorbed in a book, but bits of the stories kept bothering her. There was a girl who stopped being able to talk when her mother died. There was a girl who was separated from her family during the plague. There was a girl who was sent away to become a servant on her twelfth birthday. It probably should have been comforting to think that she wasn’t the only one alone and adrift in outer space, but it felt more like being punched in the stomach.

Sally hated sleeping with the window open (she’d read too many stories about vampires), but Rube had told her it was too hot to sleep with it closed tonight, so they’d compromised. The window was only open a crack- barely three centimetres- and that was just wide enough for the moth to get in.

Sally looked up at the window, and there it was, a fluttery tangle of brown on the windowsill. It was moving- it looked as if it was trying to get its wings into position- but there was a reddish-brown stain underneath it, smudged across the wood. Sally got up for a closer look. Something had happened to one of its… wings? Legs? There was too much blood to tell. She didn’t dare move it. If you picked insects up the wrong way, you could end up crushing them to death.

There was nothing for it- she was going to have to go and find the bathroom. She was pretty sure she remembered where it was, but that didn’t mean she had to be happy about it.

Sally opened the door, and stepped out into the cold, dark hallway. It was gloomy and weird-smelling, and the floor was all stony and cold on her feet, but at least the bathroom wasn’t that far down the hall. There was a little glass in there to keep toothbrushes in, and Sally took the brushes out and filled it up part of the way with water. After thinking about it for a moment, she took a few squares of toilet paper as well.

She hurried back to the moth. If she was careful, maybe she could clean it up. At least then she’d be able to see what had happened.

The moth hadn’t stopped moving. Sally put the glass down beside it, and dipped her finger in the water. Just a little drop. She didn’t want to soak it.

As gently as she could, she touched the moth’s side, near where the blood was but not actually on it. She couldn’t tell if it had made any difference, so she put her hand back in the glass and tried again.

It took three drops of water before she dared to dab the moth with the tissue and wipe away some of the blood, but when she did, she was relieved to see that it was only the blood that was coming away. She hadn’t pulled off any of its legs by mistake. Soon the wing was clean. Sally couldn’t see any damage. It must have been the body that was hurt.

Once she’d sponged away as much of the blood as she dared, Sally cupped her hands around the moth too see if it flew up and perched on her finger. Instead, it just fluttered for a bit, then gave up.

So, how were you supposed to look after a moth? She tapped her fingers on the windowsill, thinking. She was pretty sure that insects were cold-blooded, so she shut the window so it wouldn’t freeze. She thought about fetching a bit of cloth to put over it, like a blanket, but she didn’t know how to make sure it wasn’t too heavy. After a moment, she went to one of her bags, got out a notebook, and tore out a piece of paper. If she gave it a little paper tent, it would be in the shade when the sun came up in the morning.

Sally stayed there for another hour, keeping an eye on the moth. It wouldn’t have been polite to leave him alone in the dark, either.

(To be continued)