The sun rises over the hills. The valley is friendly and the people are happy. The birds sing. In the middle of the valley is a stately home surrounded by apple trees. It’s sunny, so things are very clean. The church bells are ringing. The maids have their hair in bunches. The grandfather of the house wanders about, micromanaging and smoking a pipe. His wife is chopping bread and us much better at it than the servants are. Said servants make the coffee while the lady of the house gives them orders. We are now on page 10. Wasn’t this supposed to be a horror story?

Anyway, there’s a christening going on. We know this because the lady of the house mentions it twice, and then the narrator mentions it a third time, in case we missed it. There is cheese. The lady of the house fetches a better plate for the cheese. There are cakes. The midwife is tired of waiting. I know the feeling. The godmother arrives, with more cake. Everyone says hello and offers her coffee, but she says no because she’s eaten already. That last sentence takes two whole pages. Two more are devoted to the fact that she then eats some food anyway. Where is this black spider, and why is it taking so long?

Some other family members show up, and have wine instead of coffee, and then everyone sets off for the christening. The mother of the baby isn’t allowed to go because that’s too common or something. The godmother flirts with all the single men. The baby gets changed. Everyone gets drunk. After the christening, and after the big meal that takes another six pages to describe, and after one of the godfathers talks like an MRA for a bit, and after they all sit under a tree, and after we’re more than a fifth of the way through the book, somebody finally- finally– asks the grandfather about the ugly black window in his house. Now the actual story can begin.

Six hundred years ago, the lord of the manor oppressed his serfs. One day, a stranger with a red beard and a feather in his cap turned up and offered them some help. He was clearly bad news, on account of the fiery crackling noises coming from his beard, but they were getting desperate. However, he asked for an unbaptised child in payment, and that was a bit much even for them. Upon hearing about this, Christine, the wife of one of the serfs, is all for agreeing to the deal and then wriggling out of it by baptising every baby immediately after birth. She goes to meet the stranger by herself, and he seals the deal by kissing her on the cheek. The favour he does them involves “two fiery squirrels,” and that’s all I’m going to say about it.

Anyway, the next time a local woman has a baby, she calls in a priest for the birth. This means telling the priest about the Faustian pact they made earlier, but he agrees to help anyway. The baby is baptised and all seems well, but Christine feels a sudden pain in her cheek. There’s now a black spot right where the stranger kissed her, and it grows a lot over the next few weeks. Another woman becomes pregnant, and the spot starts to look like a spider. When the priest arrives to baptise Baby Number Two, Christine throws herself at his feet and begs him for help, but he shoves her aside and goes to do his job. After this, all the village’s cows start dying on account of spiders crawling all over them.

Christine’s sister-in-law finds out that she’s pregnant, and is understandably stressed-out. Things are even worse than she knows, because there’s a conspiracy in the village to take the baby away and give it to the stranger. Even her husband’s in on it. When the baby is born, the husband drags his feet on the way to fetch the priest, giving Christine enough time to pounce on his wife and steal the baby as soon as it’s born. A massive storm starts, and the priest sets out through it like an action hero. He catches Christine in the act of giving the baby to the stranger, and splashes all three of them with holy water. The stranger is swallowed up by the earth, so that’s OK, but Christine turns into a giant spider and poisons the priest and the baby to death. Her third victim is the treacherous husband, which serves him right.

She then happily settles into terrorising the village for the next week or so, though she does at least have the decency to kill the evil lord of the manor while she’s at it. People try to run away or throw rocks at her, but end up getting killed for their trouble. Eventually, Christine’s sister-in-law comes up with a plan to imprison her in a window post. It kills her and now her two surviving children are orphans, but she manages it.

We then go back to the frame story and get another long list of food. Somebody asks the grandfather if it’s safe to have a window with a spider-demon in it in the house. He says it’s fine. They have some roast meat, sweet tea and wine. Everyone’s still freaked-out about the spider story, so the grandfather tells them about a time when the spider escaped.

This happened a few generations after the spider was imprisoned, when the descendants of Christine’s sister-in-law became arrogant and started dressing fancy. The homeowner’s wicked wife and mother got him to build them a new house without a spider demon in it. The nerve. To make matters worse, the servants stayed in the old house and had food fights. One of them attacked the window with a knife, after which his friends dared him to break it, so he did. The spider got out and killed everyone except the owner, Christen, who was at church at the time. (Incidentally, there are three named characters in this story, and two of them are called Christine and Christen. It’s quite distracting.) (The third is the treacherous husband from earlier. He was called Hans.)

The spider went on another rampage, which went on until a madwoman ran into Christen’s house and gave birth to a baby, who Christen instantly took to the church and had baptised. The spider wasn’t having that, so it went to pounce on him while he was on the road. Of course, this meant that he could grab it and put it back in the window in exactly the same way his ancestor did, which just goes to show than demon spiders aren’t very good at learning from their mistakes. The end.

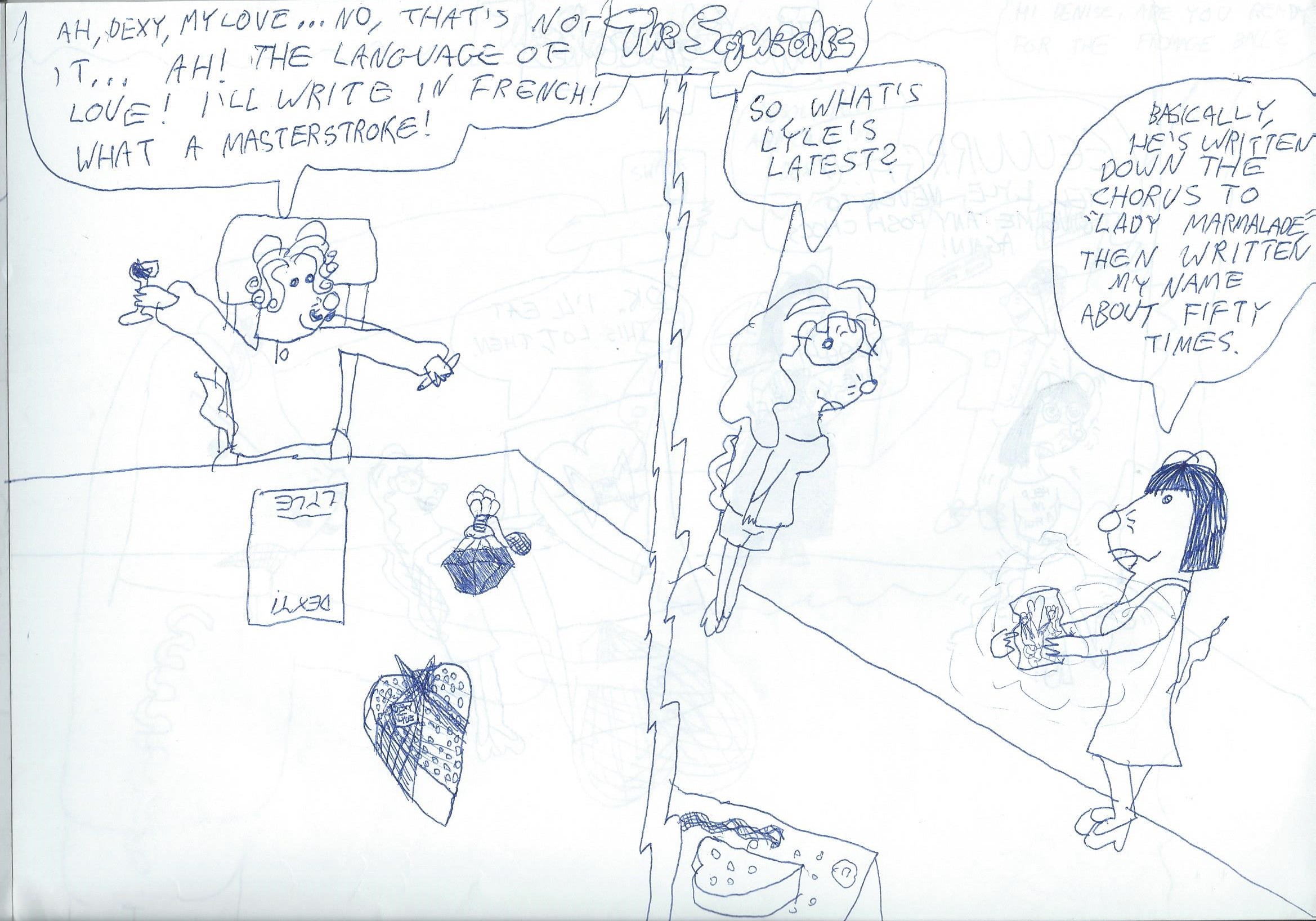

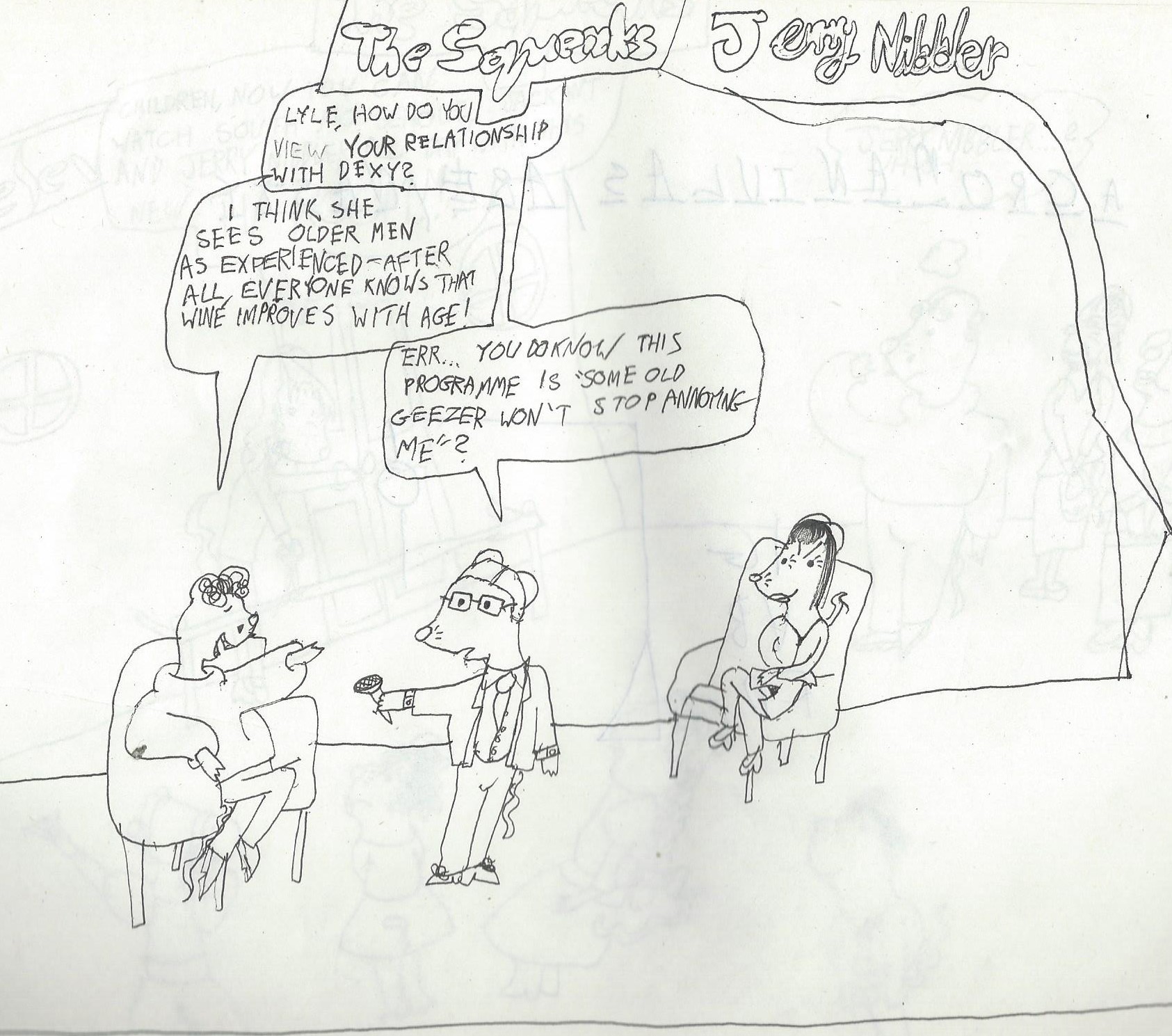

The above is a cartoon I drew when I was fourteen. Clearly, my Year Nine rough book deserved excited back-cover cover quotes from memoirists who fib a lot.

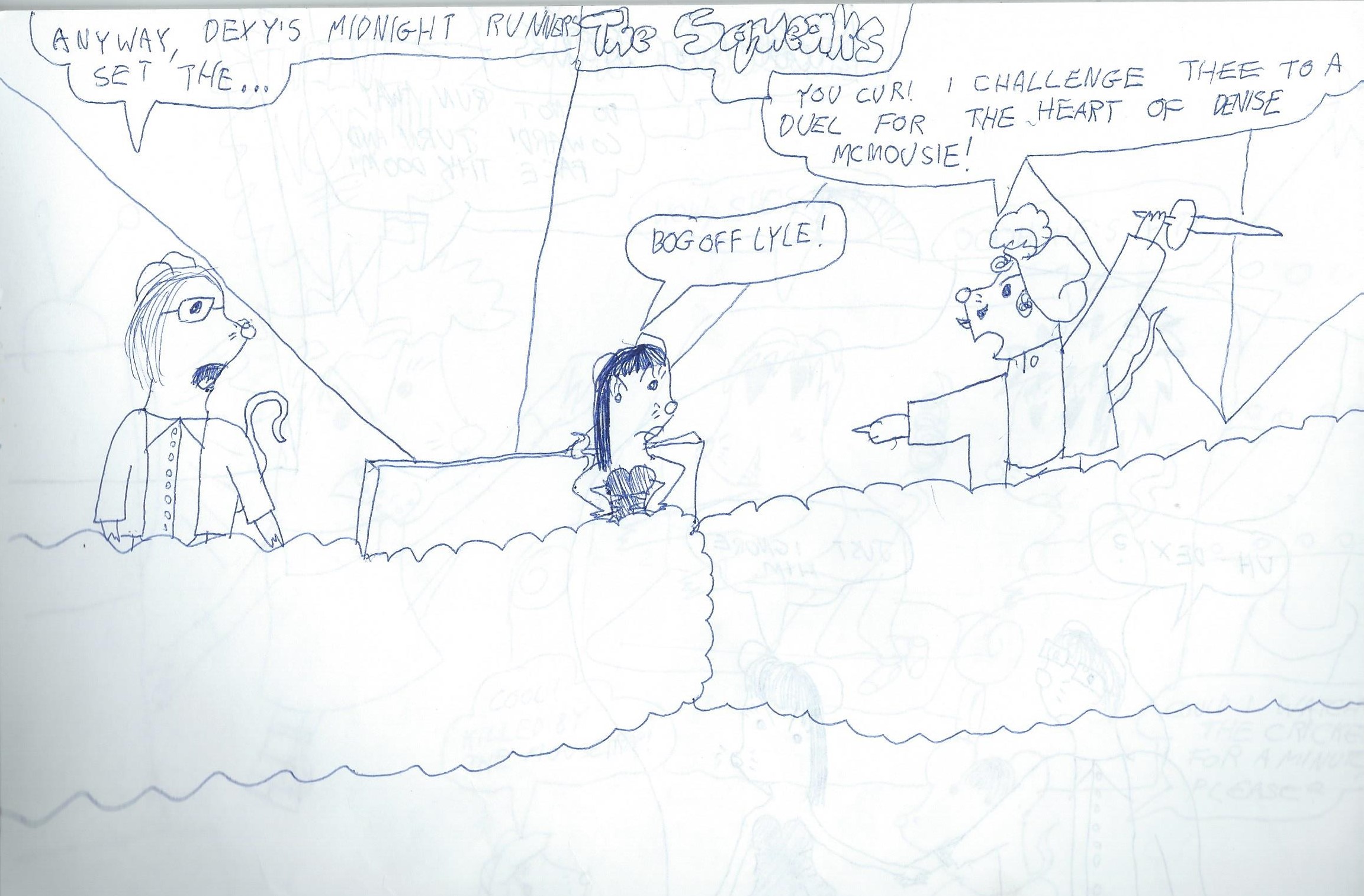

The above is a cartoon I drew when I was fourteen. Clearly, my Year Nine rough book deserved excited back-cover cover quotes from memoirists who fib a lot.